February 24, 2022, will be a turning point in history. It was the day of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine and the most significant geopolitical event of the past year. This war was, without exaggeration, the bloodiest military conflict in Europe in decades. However, it is the first major hybrid war that uses cyberspace as a full-fledged battlefield in addition to the main kinetic fronts. Of all of this, several important points can be made about the collateral cyber damage, viz:

- The effectiveness of destructive malware

- The attribution of cyber activity in wartime

- The distinction between nation-state, hacktivism, and offensive cybercriminal activity

- Cyber warfare and its impact on defense pacts

- The ability of cyber operations to engage in tactical warfare and necessary training

The impact on global cyberspace is already visible in some areas.

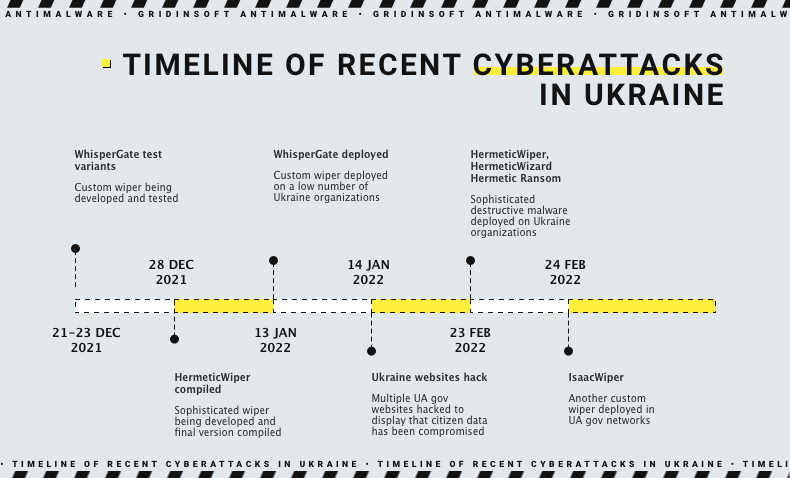

Wipers comeback

Wiper is a malware that disrupts the operation of target systems as it can delete or corrupt important files, though its use is relatively rare. However, wiper malware has become much more widespread over the past year, not just in Eastern Europe. For example, at the beginning of the Russian-Ukrainian war, the number of cyber attacks on Ukraine by malicious actors affiliated with Russia increased dramatically. Before the full-scale ground invasion, pro-Russian hackers used three wipers – HermeticWiper, HermeticWizard, and HermeticRansom – and a little later, in April, hackers used Industroyer. This is an updated version of the same malware used in a similar attack in 2016. Thus, at least nine wipers have been deployed in Ukraine in less than a year. They were developed by Russian secret services and use different wiping and evasion mechanisms.

Multi-pronged Cyberattacks

Let’s look at the vector of cyberattacks in the Russian-Ukrainian war. Same as any other attack within the war course, they can be divided into two types – strategical and tactical. The first type of cyber attack is aimed at causing widespread damage and disrupting the daily lives of civilians. In turn, the second type of attack is more targeted, coordinated with real combat operations, and aimed at achieving tactical goals. Such goals may include:

- Disabling or disrupting critical military infrastructure systems

- Hacking into and infiltrating military organizations’ networks

- Launching a disinformation campaign

- Cyber espionage

Strategical attacks

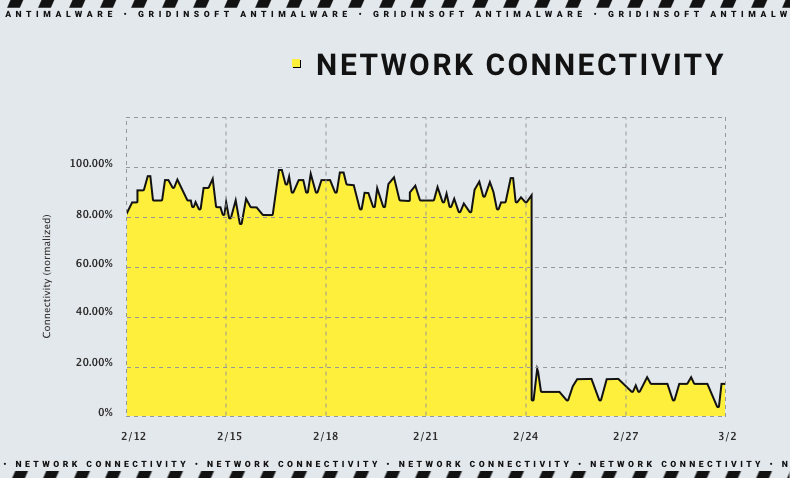

A few hours before the ground invasion of Ukraine, hackers launched a cyber attack on Viasat. This attack aimed to interfere with satellite communications, which provide services to both military and civilian organizations in Ukraine. In this attack, hackers used a wiper called AcidRain, designed to destroy modems and routers and disable Internet access for tens of thousands of systems.

In addition, even before the full-scale invasion, Ukrainian government agencies, such as Diia, and some banks were subjected to cyberattacks. The purpose of these attacks was to cause the Ukrainian population to distrust the government. Another curious incident took place on November 3, 2022. At that time, a certain “Joker DNR” hacked into the Instagram page of Valery Zaluzhny, the commander-in-chief of the AFU, installing a photo of the Russian dictator on his profile photo. Later, an image appeared on the page with the caption, “So, I confirm that Joker DNR infiltrated DELTA“. However, Ukrainians ridiculed the incident rather than taking it seriously. This is far from the only case of hacking into Ukrainians’ social networks. Since the start of the full-scale Russian-Ukrainian war, Ukrainian users have periodically received phishing emails asking them to click a link.

Tactical cyberattacks

Any tactical, high-precision cyber attack requires careful preparation and planning. Prerequisites include accessing target networks and creating customizable tools for different attack stages. One example of a coordinated tactical attack occurred on March 1. That day, Russian missiles struck the Kyiv TV tower, causing television broadcasts in the city to stop. Next, hackers orchestrated a cyber attack to amplify the effect.

Adaptive cyberattacks

According to the available data, the Russians were not preparing for a lengthy campaign—the abrupt change in the characterization of cyber attacks in April evidence this. They shift from fairly precise attacks with clear tactical objectives to less elaborate ones. Similar to the change of tactics on the battlefield, where Russian troops were rebuffed with dignity and decided to fight civilians, the hackers also changed their vector – they tried to harm Ukrainian civilians. The use of multiple new tools and wipers was replaced by detected capabilities using already-known attack tools and tactics, such as Caddywiper and FoxBlade.

The head of Britain’s intelligence, cybersecurity, and security agency called Ukraine’s response “the most effective defensive cyber activity in history. This is not surprising, as part of Ukraine’s success is because it has been repeatedly subjected to cyber attacks since 2014. The impact of the Indistroyer2 attack on the energy sector in March 2022 is evidence of this because compared to the first deployment of Industroyer in 2016, the effect in March was negligible. In addition, Ukraine has received significant external assistance to repair the damage caused by these cyberattacks. For example, foreign governments and private companies helped Ukraine quickly move its IT infrastructure to the cloud. As a result, data centers were physically removed from combat zones and received additional layers of protection from service providers.

Shift in the focus

Since September, data show a gradual but significant decrease in cyber-attacks against Ukrainian targets. Instead, the number of attacks on NATO members has increased significantly. Moreover, while the number is negligible in some countries, in others, the number of attacks has increased by almost half:

- U.S. by 6 percent

- United Kingdom by 11%

- Poland by 31%

- Denmark by 31%

- Estonia by 57%.

This suggests that Russia and related groups have shifted their attention from Ukraine to NATO countries that support Ukraine.

The New Era of Hacktivism

A new era of hacktivism began with the creation and leadership of the “IT Army of Ukraine,” composed of volunteer IT specialists. Whereas hacktivism used to be characterized by free cooperation between individuals in ad hoc interactions, new-era hacktivist groups have significantly increased their organization and control and now conduct military-like operations. The new mode of operation includes recruitment and training, intelligence and target allocation, tool sharing, etc. Nevertheless, anti-Russian hacktivist activity continued throughout the year, affecting infrastructure, financial, and government organizations. Since September 2022, the number of attacks on organizations in Russia has increased significantly, especially in the government and military sectors.

Not all hacktivists are good

Unfortunately, not all hacktivists have good intentions. For example, while groups such as Team OneFist rigorously enforce the rules of war and take steps to avoid potential damage to hospitals and civilians, the pro-Russian group Killnet carried out targeted DDoS attacks on critical infrastructure in the United States. Predictably, their primary targets were not military installations but U.S. medical organizations, hospitals, and airports. In addition, most new hacktivist groups have a clear and consistent political ideology tied to government narratives.

As a result, pro-Russian hacktivists have shifted their focus from Ukrainian targets to NATO member states and other Western allies. For example, another Russian-linked hacktivist group, NoName057(16), attacked the Czech presidential election. In addition, the hacktivist group From Russia with Love (FRwL), also known as Z-Team, deployed Somnia ransomware against Ukrainian targets. In turn, the CryWiper malware was deployed against municipalities and courts in Russia.

Hacking Russia was off-limits before Russian-Ukrainian War

Some cybercrime organizations have been forced to join the nationwide effort and curtail their criminal activities. Attacks on Russian enterprises, once considered impregnable by many cybercriminal organizations, are now on the rise. Russia is struggling with hacking attacks caused by the government and its criminal activities. In addition, other countries have also stepped up their spying activities in Russia to attack Russian state defense institutions. For example, Cloud Atlas constantly attacks Russian and Belarusian organizations.

War impact to other regions and domains

Against the backdrop of the Russian-Ukrainian war, wiper activity began to spread to other countries. For example, Iranian-linked groups have attacked facilities in Albania, and the Azov ransomware has spread worldwide. However, Azov is more of a destructive wiper than a ransomware program because it does not provide for decrypting and restoring encrypted data. Various state actors have also taken advantage of the war to advance their interests. For example, several campaigns by different APT groups have used the ongoing battle between Russia and Ukraine to intensify their activities. The Russian-Ukrainian war has dramatically affected cyber tactics in many areas. Undoubtedly, as long as the war continues, its events will affect other regions and locations.